The Wild Hope video series spotlights some of the most impactful conservation success stories happening around the world today, but these modern triumphs didn’t develop in isolation. They build on decades of hard-won victories and centuries of wildlife management plans, environmental policies, and conservation activism that have brought hundreds of species back from the brink. Many well-known plants and animals that we take for granted today, including the American alligator, humpback whale, and bald eagle, were once headed toward extinction until passionate and dedicated conservationists intervened and changed the tide.

In our new illustrated Conservation Comeback series, produced in partnership with the design team at Peppermint Narwhal, discover the threats, the solutions, and the success stories behind some of the world’s most iconic animal recoveries.

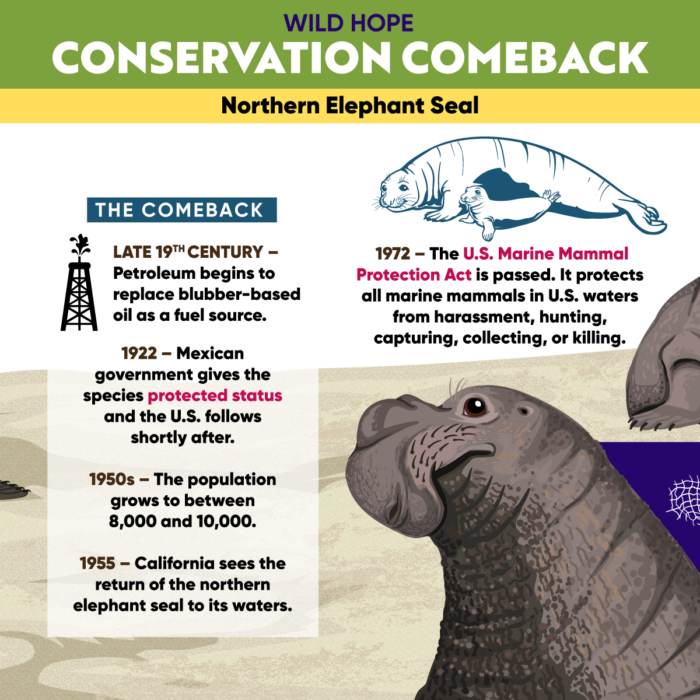

The Northern Elephant Seal

Along the Pacific coastlines of North America, the northern elephant seal is now a common sight — but at one point it was so rare that the species was officially (and wrongfully) declared extinct. Today the large seal’s current population stands at 160,000 and growing, but in the 19th century it was critically overhunted for its oil-rich blubber. If it weren’t for the decreasing demand for blubber-based fuel and subsequent policies enacted to protect the species, the northern elephant seal might not swim in our waters today.

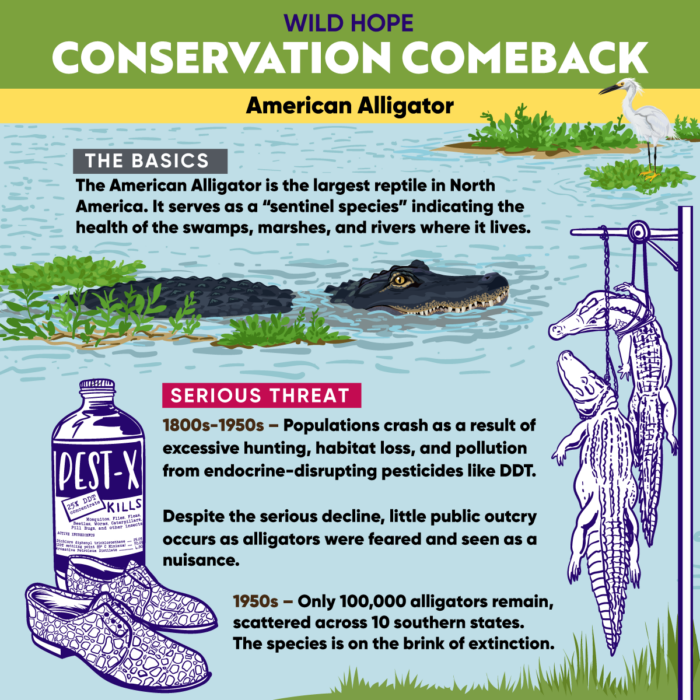

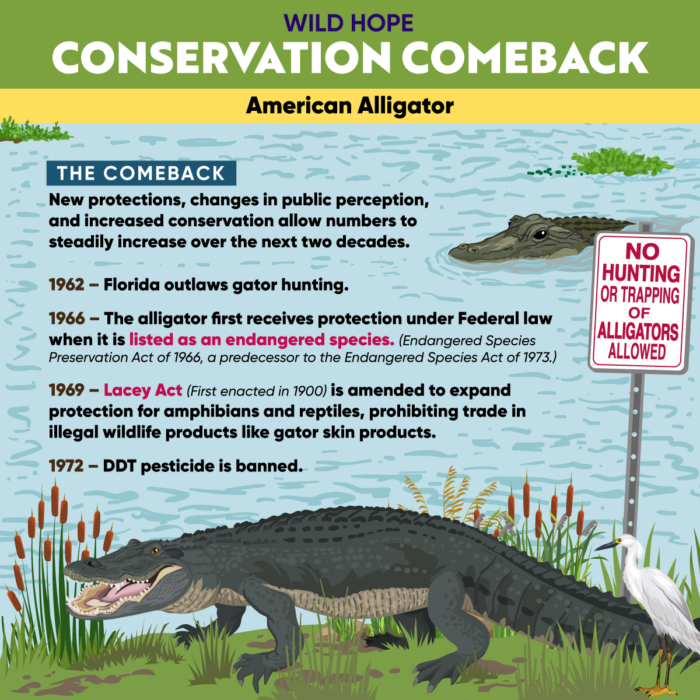

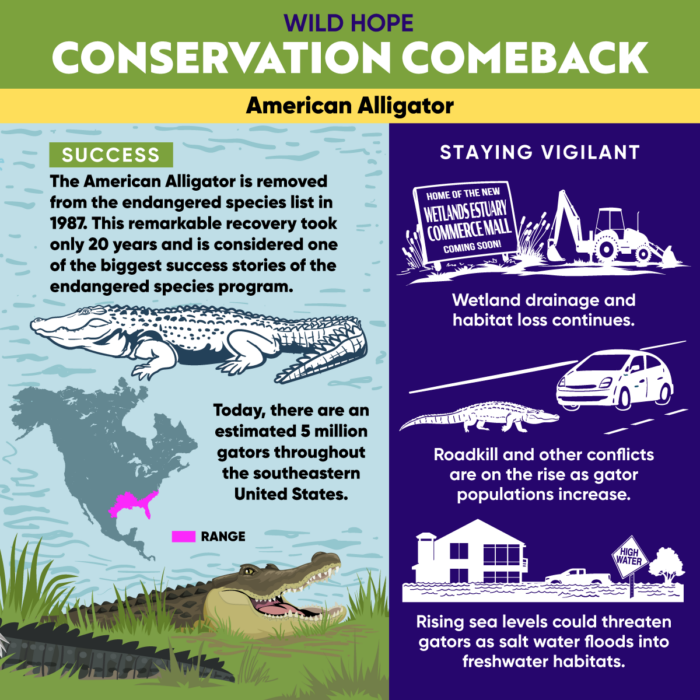

The American Alligator

The recovery of the American alligator is considered one of the greatest endangered species success stories. By the 1950s, decades of overhunting, critical habitat lost, and pollution from pesticides brought the gator dangerously close to extinction. The tide finally began to turn in 1962 when Florida lawmakers outlawed gator hunting in the state. The species was granted federal protection soon after, in 1966. These measures paid off: today there are an estimated 5 million American alligators thriving once again in the southeastern United States.

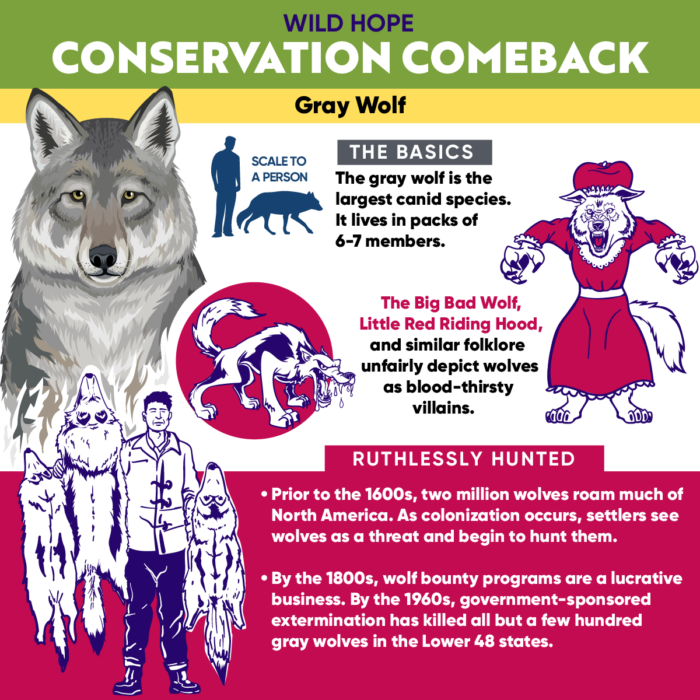

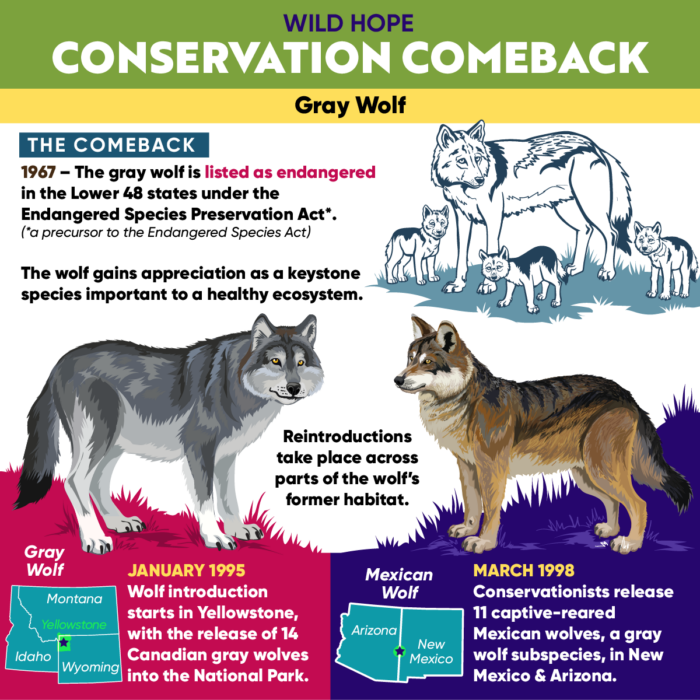

The Gray Wolf

Our relationship with gray wolves is a complicated one, spanning centuries of tension and hostility. In North America, wolves were vilified by European settlers beginning in the 1600s due to the perceived threat that the canines posed to livestock. As a result, wolves became the target of extensive hunting and bounty programs. It wasn’t until 1967 that the species was officially listed as endangered in the U.S. and broadly recognized as an asset to healthy, balanced ecosystems. In the 1990s, wolf populations were reintroduced to wild areas including Yellowstone National Park. Their recovery has been slow, but today there are about 6,000 gray wolves in the lower 48 states — and their numbers are increasing in many parts of their range.

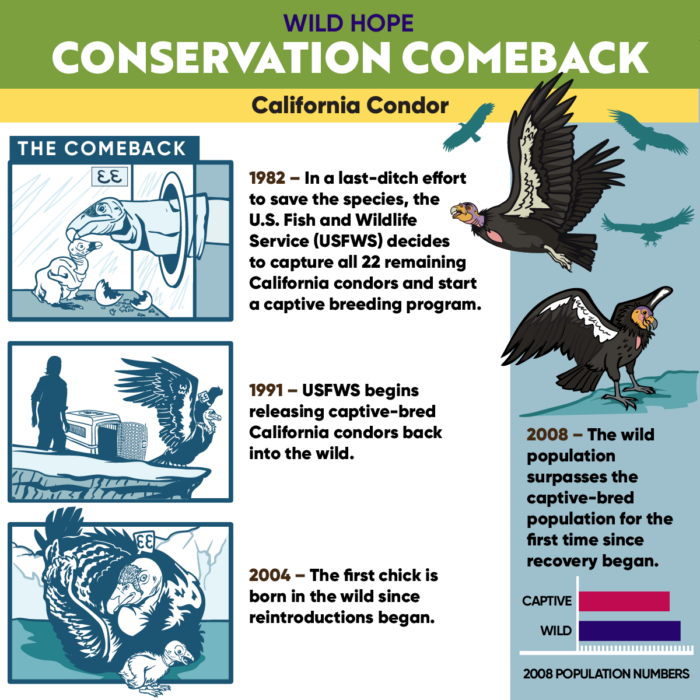

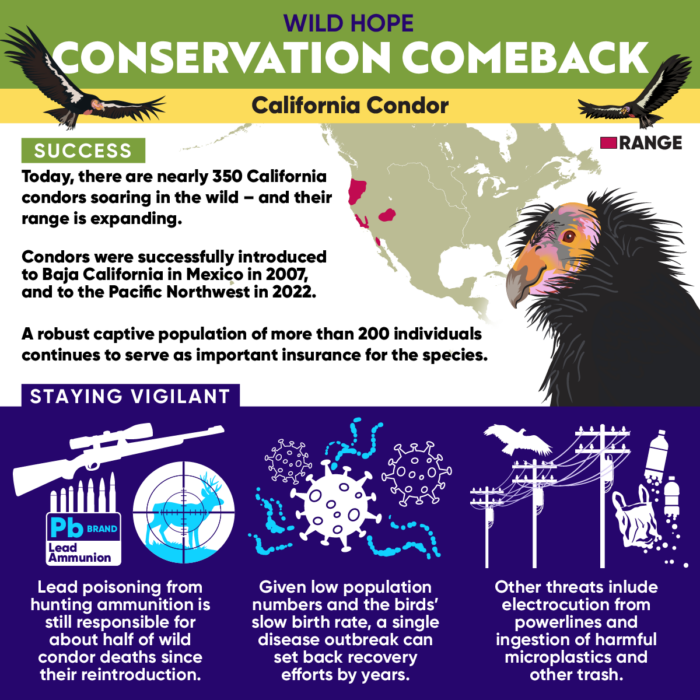

The California Condor

The California condor is a North American wildlife icon — it is the continent’s largest land bird and one of nature’s most industrious scavengers. The species was left in dire straits when numbers plummeted after European colonization, with only 60 condors remaining by 1967. The decline was driven by poisonous lead fragments from bullets left behind in gut piles, which the condors ingested while feeding on animal remains. In 1982, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service launched a last-ditch effort to save the species through captive breeding. Over the next several decades, this captive breeding program slowly began to rebuild the dwindling population — and in 1991, conservationists released captive-bred condors back into the wild for the first time. The condor’s journey isn’t over, as lead shot continues to threaten the species, but the success is still monumental: today there are 350 wild California condors, and their range is expanding.

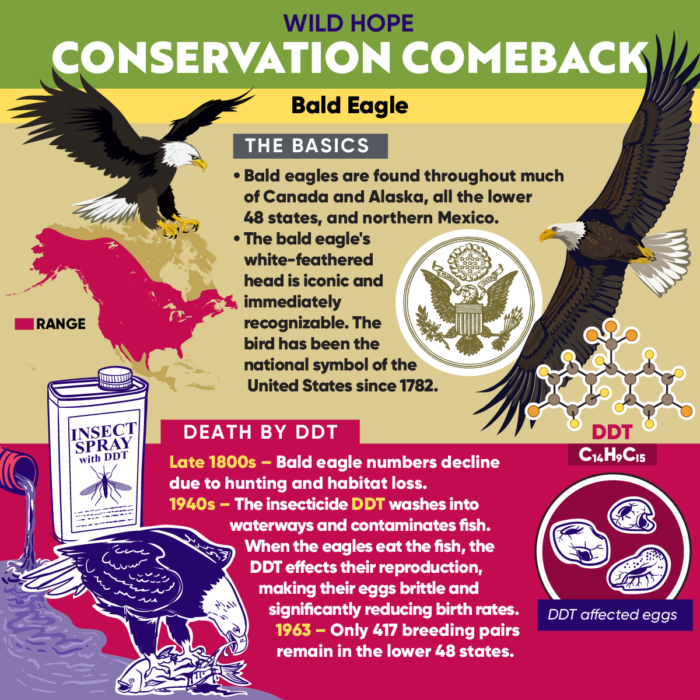

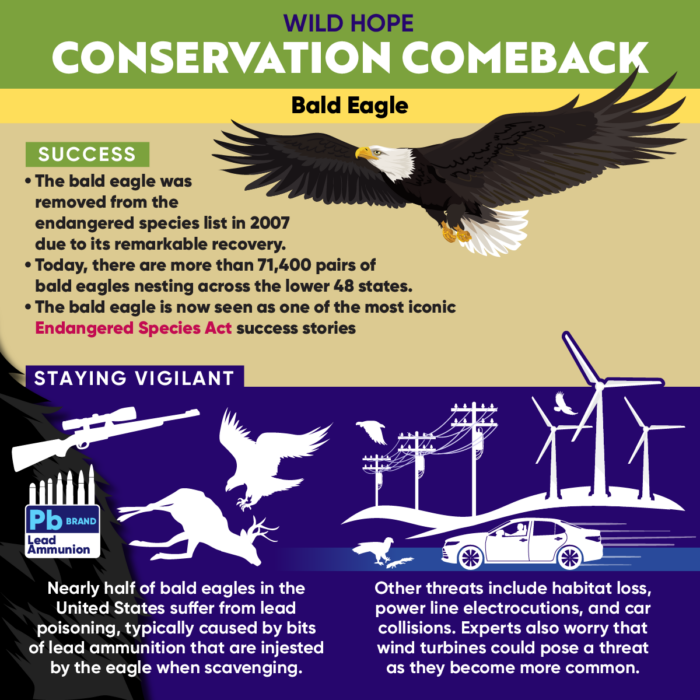

The Bald Eagle

The bald eagle has been a national symbol of the United States since 1782 — but not that long ago, this iconic species was on the verge of a complete extinction. In the late 1800s the eagle population had already begun to decline due to hunting and habitat loss, but the real threat came in the 1940s with the introduction of the pesticide DDT. Chemical runoff would contaminate fish, and then once ingested by the eagles, would cause the eagles to lay brittle eggs that would break before hatching. In 1963, there were less than 500 breeding pairs in the lower 48 states.

DDT was banned in 1972 and the bald eagle was officially listed as endangered in 1978, allowing their recovery to take off. Over the next 20 years, the population rebounded — and in 1995 the species’ was removed from the endangered species list entirely. Today, their numbers are thriving once again, with more than 70,000 breeding pairs of eagles observed in the lower 48 states. The bald eagle is seen as one of the most iconic Endangered Species Act success stories.

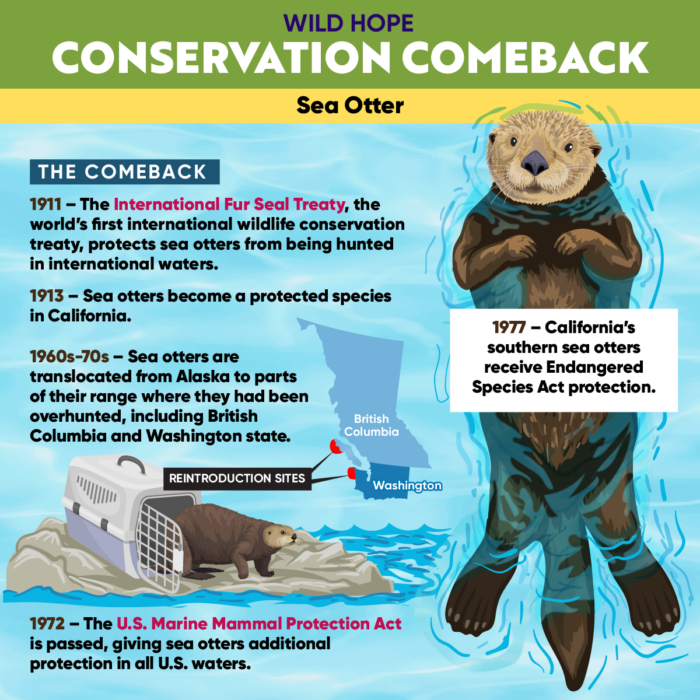

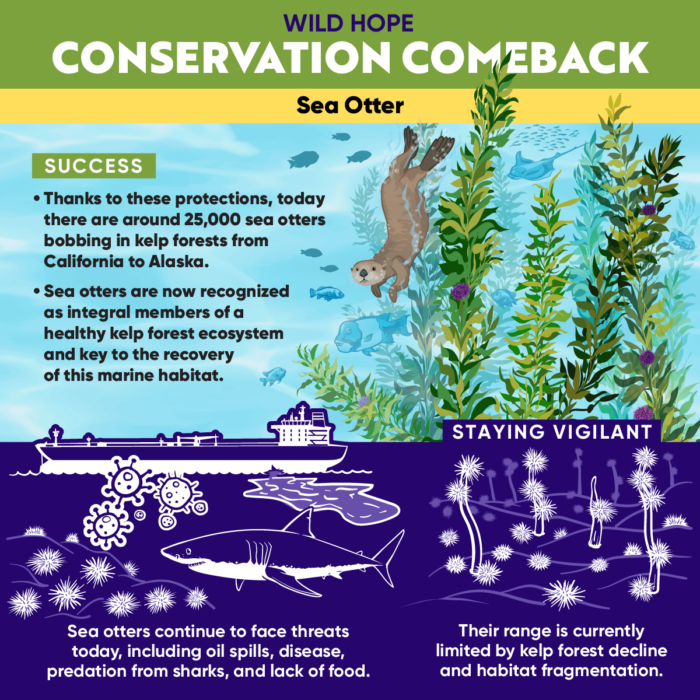

The Sea Otter

Sea otters are a marine mammal beloved by many, but it wasn’t long ago that they teetered on the brink of extinction. The international fur trade decimated sea otter populations starting in the 1700s, and by the early 1900s, their wild population fell to less than 1% of their original numbers. Sea otters are a keystone species, and their presence in coastal kelp forests is critical to keep sea urchins under control — losing the otters could have resulted in a massive collapse of coastal ecosystems.

Lucky for the otters — and for otter fans worldwide, the International Fur Seal Treaty signed in 1911 began protected sea otters from being hunted in international waters, and two years later, they became a protected species in California. After the eventual signing of the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972, and decades-worth of translocation of otters from Alaska to coastlines further south, the population has made an astounding recovery. Now, there are over 25,000 sea otters bobbing around kelp forests from California to Alaska, and their role as keystones to protect kelp forest ecosystems has been widely recognized in the conservation community.

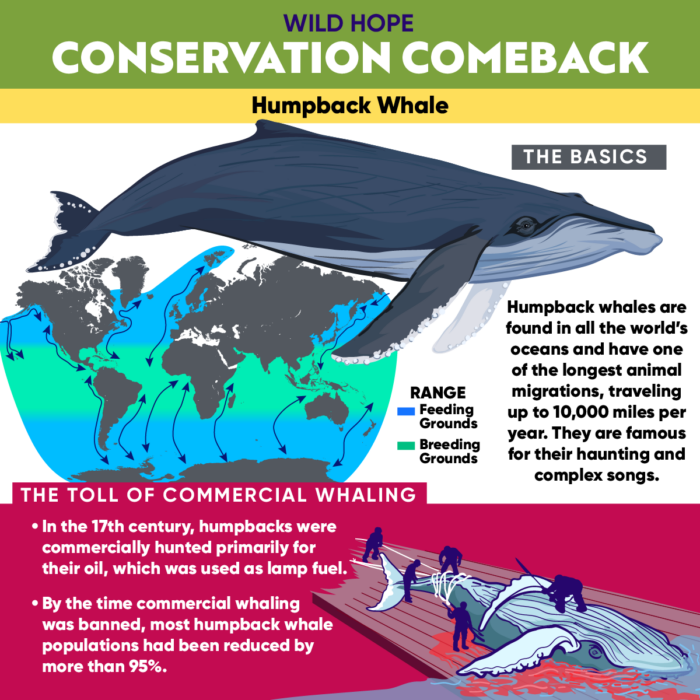

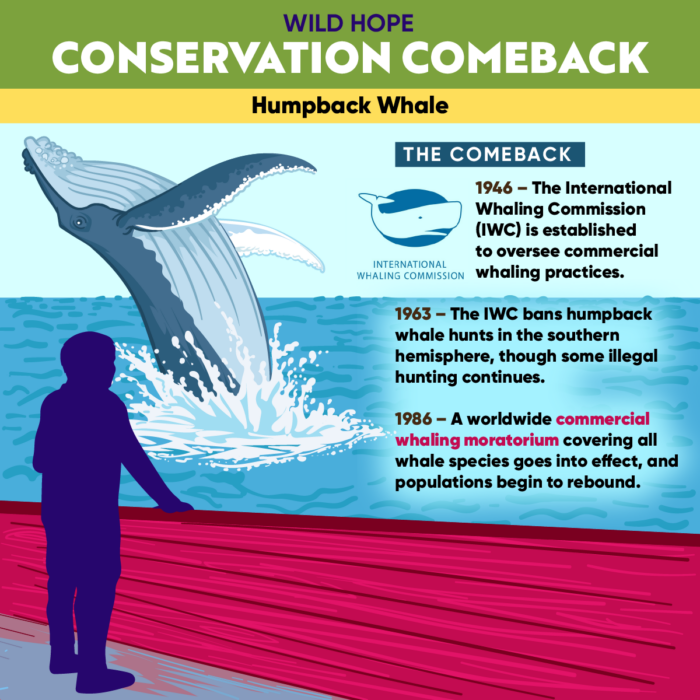

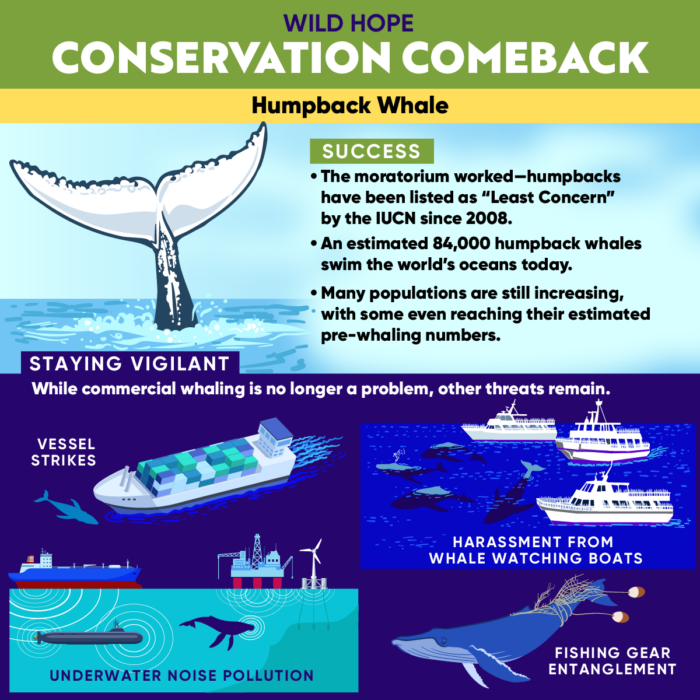

The Humpback Whale

Humpback whales are truly a global species. These mammals have one of the longest migrations around, traveling up to 10,000 miles in a single year — and their beautiful, complex songs are heard by sailors and tourists in every corner of the globe. In the 17th century, humpback whales were hunted primarily for their oil, which was used as lamp fuel. By the time whaling was officially banned, humpback populations had been reduced by 95%.

The comeback was slow, beginning in 1946 with the establishment of the International Whaling Commission to oversee whaling practices. Hunting humpbacks was banned in 1963, and in 1986, a worldwide commercial whaling moratorium gave populations another foothold on the path to recovery. Today, an estimated 84,000 humpbacks swim the world’s oceans, and many populations are still on the rise, even approaching pre-whaling numbers.

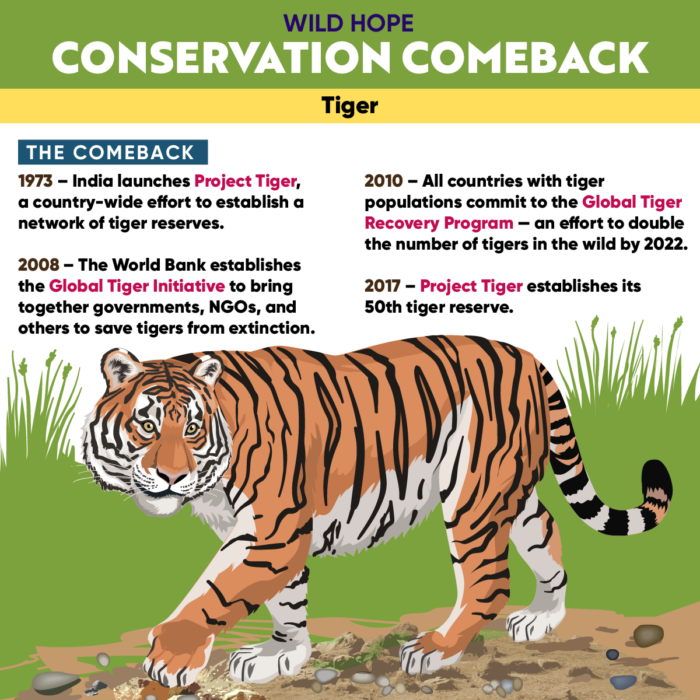

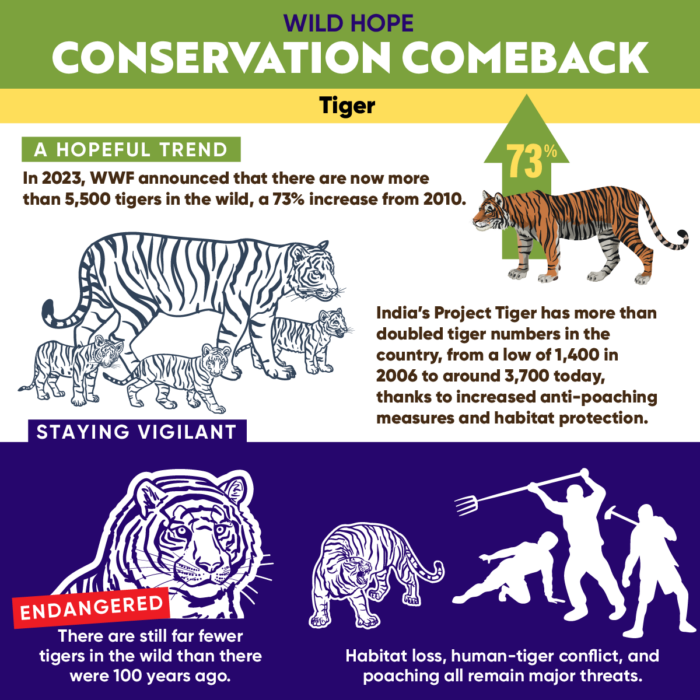

The Tiger

Tigers are one of the most iconic faces of wildlife conservation worldwide. These species are still endangered, but indeed on the rise — although it wasn’t long ago that tiger populations teetered on the edge of extinction.

Due to a long history of hunting and habitat loss, tigers across Central and Southeast Asia had once fallen to only 5% of their original numbers. The long journey to restore dwindling tiger populations began in 1973 with the rollout of India’s Project Tiger, with the aim to establish tiger reserves across the country. In the decades to follow, many other nations followed in India’s footsteps by joining the Global Tiger Recovery Program in 2010. Just 13 years later, the WWF celebrated more that 5,500 wild tigers — an increase of 73% since the launch of the Program.

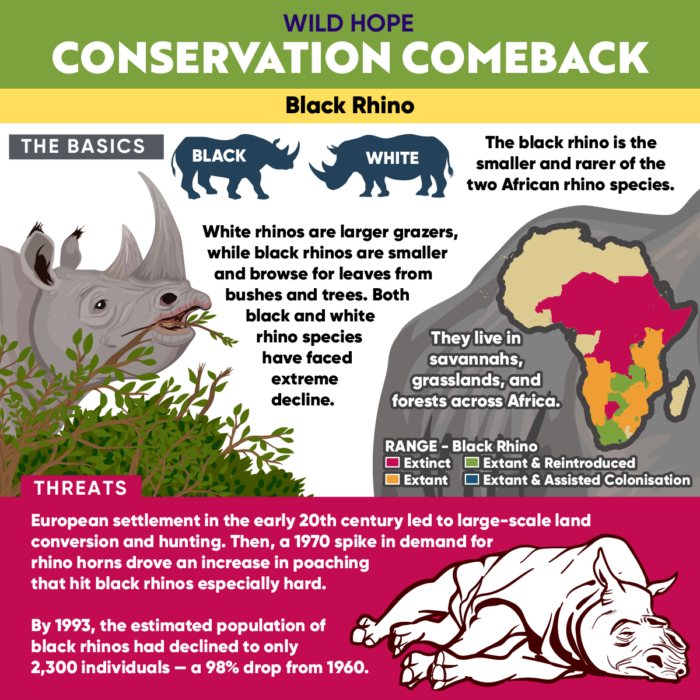

Black Rhinoceros

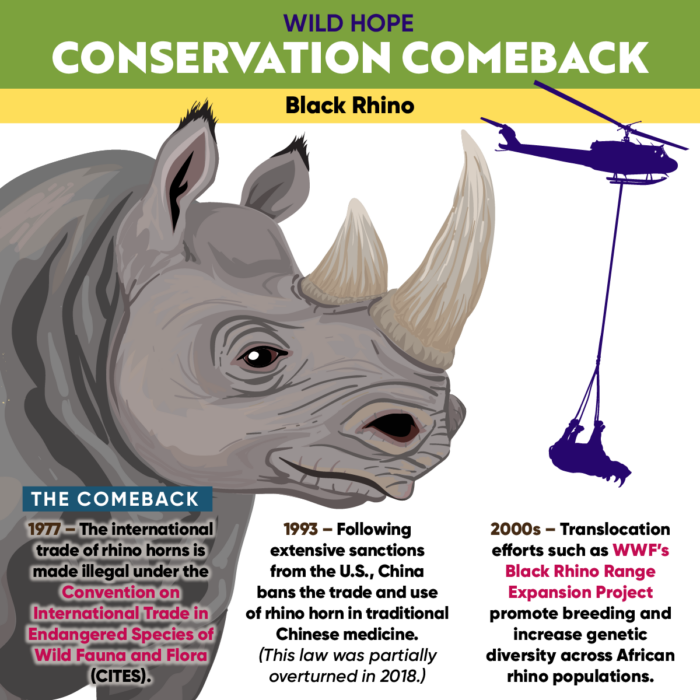

The smaller and rarer of the two African rhino species, the black rhinoceros has faced steep decline since the early 20th century. The situation became dire in the 1970s, when poaching for the rhino’s horns decimated the population. By 1993, the black rhino population had declined by over 98%.

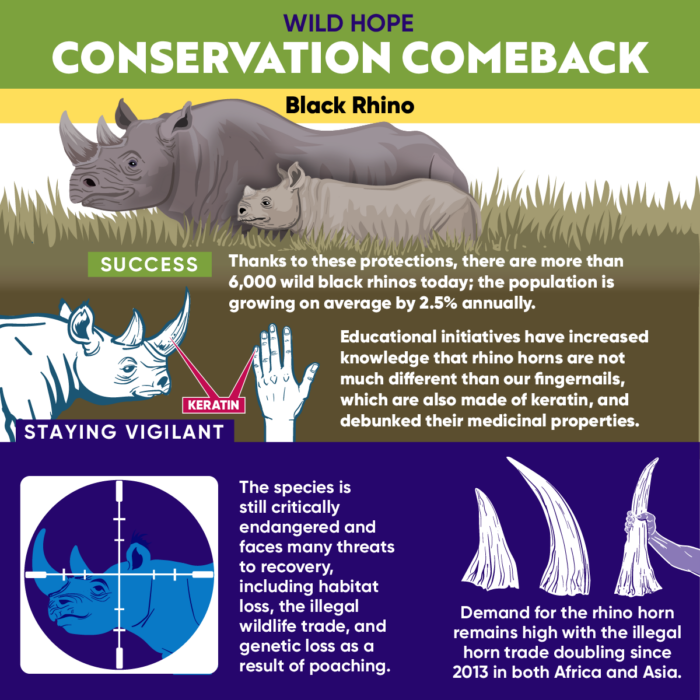

Extensive sanctions to ban the trade of rhino horns eventually slowed the decline of the species. In the 2000s, translocation efforts (like the Black Rhino Range Expansion Project) promoted breeding and genetic diversity between the remaining rhino colonies. As a result, the number of wild black rhinos is up to 6,000 and increasing 2.5% each year.

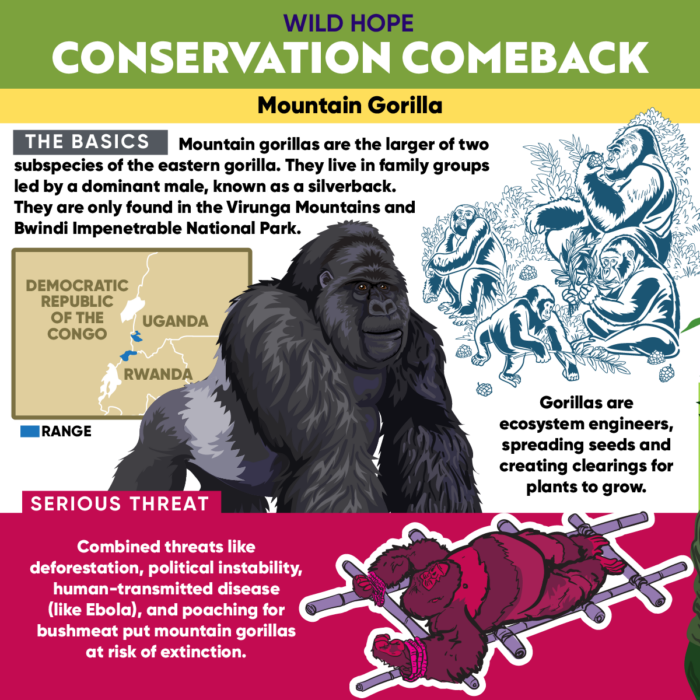

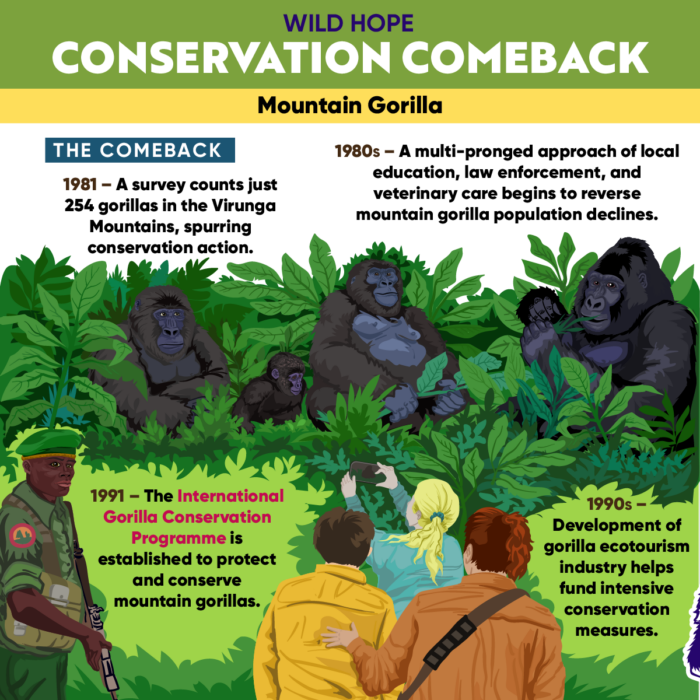

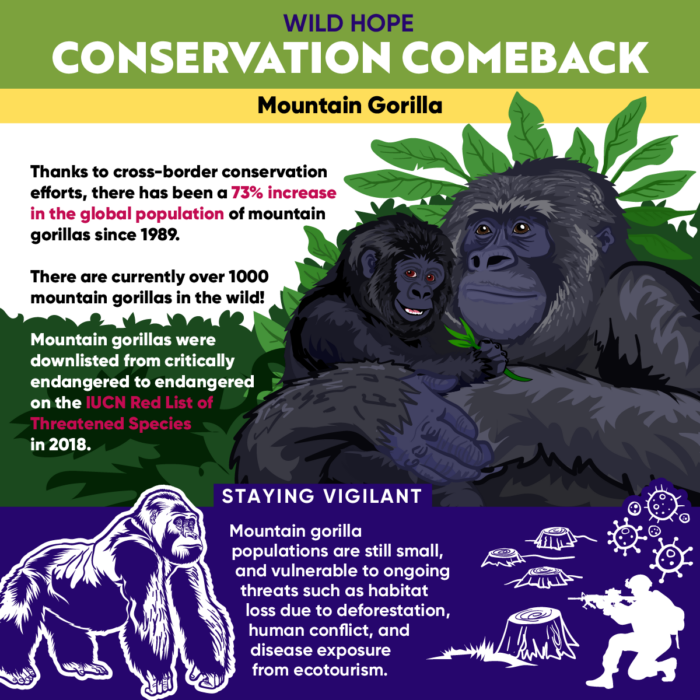

Mountain Gorilla

The mountain gorilla, a critically endangered subspecies of the eastern gorilla, has faced a dramatic decline over the past century. By the early 20th century, their population had dwindled due to habitat loss, poaching, and the spread of diseases from humans. At its lowest point in the 1980s, the mountain gorilla population was reduced to fewer than 250 individuals, with their survival hanging by a thread.

In response, conservation efforts, including anti-poaching laws, veterinary care, and community-based initiatives, have helped the species recover. These efforts have more than doubled their numbers, with around 1,100 mountain gorillas now living in the wild. While their recovery is promising, they remain at risk and require ongoing protection to ensure their survival.