Landowners around the world are returning their fields to nature in a hopeful trend often referred to as rewilding. In 2021, an Oregon farmer in the Klamath River Basin decided to take the plunge and converted 70 acres of barley on his 400-acre farm back to the wetland habitat that was there before the area was drained for farmland. Now, just two year later, the new wetland supports migrating waterbirds and endangered fish, reports The Guardian. It also acts as a buffer to keep harmful pollution from farm fertilizers from seeping into the adjacent Klamath Lake.

While this wetland is still young, it could provide a roadmap for other farmers in the Klamath River Basin, which has lost more than 95 percent of its precolonial wetlands. That’s the hope of the Wetlands Initiatives, a nonprofit that is working to make farm-based wetlands commonplace in the future, acting as a boon to biodiversity and a natural way to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

In the US alone, an estimated one billion birds die each year when they collide with windows. Now, two organizations help pave the way to a bird-friendly future.

Dr. Dustin Partridge is the Director of Conservation and Science at NYC Bird Alliance (formerly NYC Audubon), a nonprofit that protects wild birds and their habitats in New York City.

Brian Evans is a migratory bird ecologist at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, which studies and educates the public on the ecology of migratory birds.

Sara Hallager serves as curator of birds at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute.

Making windows safe for birds at home is easy! Some treatments look like little dots, others use stretches of tape – and even temporary solutions like paint or soap make a difference!

The National Zoo in Washington DC had 10,000 square feet of glass that posed a threat to migrating birds – so experts at the Zoo began the massive effort to treat every pane of glass they could!

There are many ways to reduce bird-window collisions at home and in your community.

With its growing population and wealth of wildlife, India is at the forefront of creative, community-based solutions to human-wildlife conflict.

Using satellite trackers, scientists have discovered the whereabouts of young sea turtles during a key part of their lives.

For decades, conservationists have pushed for changes to U.S. 64, a busy two-lane highway to the popular Outer Banks that runs straight through the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge — one of just two places in the world where red wolves run free. They may finally be getting their wish.

Brazil's Atlantic Forest is often shadowed by the vast Amazon, but it is just as biodiverse and at greater risk of vanishing without conservation action.

The Hawaiian archipelago is a tropical volcanic island chain with high biodiversity on land and in the surrounding waters of the Pacific Ocean. The mountainous terrain is home to many species found nowhere else on Earth, including 5000 insect species, 1000 plant species, 145 fish species, and 60 bird species. But Hawai’i’s wildlife has been […]

About 21.5 million acres of the Western United States are nationally protected, and thousands are being managed or co-managed by Native American tribes reclaiming ancestral relationships with native plants and animals. It’s no surprise, then, that Wild Hope hit a rich vein of conservation stories grounded in the West.

As we close out the year here at WILD HOPE, we’re looking back on a whole forest of stories from 2024 that represent milestones, breakthroughs, and remarkable innovation in the world of conservation and planetary health.

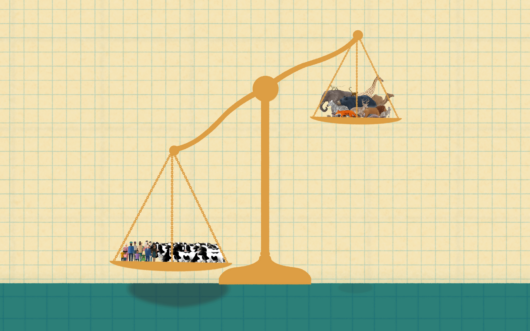

The planetary impact of largescale animal agriculture on biodiversity is immense – from the release of greenhouse gases, to the demand for available land at the expense of native ecosystems. Studies show that 75% of all agricultural land on earth is committed to raising livestock, and replacing meat products with plant-based foods could free up […]

Innovative biochemist Pat Brown is the man behind the Impossible Burger. Now, he's set his sights on a rewilding project on a ranch in Arkansas.

Efforts to break our dependence on large-scale animal agriculture are real… and they're working on two fronts! First to create alternative options for protein that don't come from animals, and second, to transform defunct cattle ranches into revived forested ecosystems.

Scientist Pat Brown has made a name for himself in biochemistry, and more recently in the initiative to reduce humanity’s reliance on animal agriculture. Throughout his journey, he’s championed one particular philosophy: “Blast Ahead!”

Biology Pat Brown has influenced the fields of biochemistry, virology, and genomics throughout his career. Now, the renowned scientist sets his sights on the largest problem of all: climate change.

Bringing biodiversity back to a clearcut ranch in Arkansas is a daunting task, but the mission is clear: use trees and native plants as powerful tools for capturing and sequestering carbon.

When Pat Brown recognized that replacing the use of animals as a food technology could rapidly arrest global heating and reverse the global collapse of ecosystems and biodiversity, Pat founded Impossible Foods, a company that makes delicious, nutritious, affordable and sustainable meats directly from plants.

It was a late-career epiphany that led “wacky genius” Pat Brown to abandon his academic career and commit himself to fighting global warming and biodiversity collapse. He did it, against all odds, by developing a surprising product: the revolutionary and delicious plant-based Impossible Burger.

The red-cockaded woodpecker, a longleaf pine specialist that lives in the southeastern U.S., was one of the first species listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

Economic growth and wildlife conservation often run in conflict, but Mozambican scientist Cesária Huo hopes to support a new sustainable and economically viable model for harvesting a potent natural resource: bat guano.

To successfully protect the wildlife in Gorongosa National Park, biologists like Cesária Huo know to first support the communities that call the park home.

Researchers survey the bats in Mozambique's Cheringoma caves looking for insectivorous species known to produce the best quality guano that can be harvested as fertilizer.

Cesaria Huo is a conservation biologist focusing on bat research in Gorongosa National Park.

From leaving the leaves to making a pumpkin bird feeder, here are a few suggestions from wildlife experts for a sustainable spooky season.

Pawpaws are in season, ocean waves gain rights, and salmon can swim freely in the Klamath

It hasn’t been easy to convert the fishing community of Gujarat, India to be whale shark allies — but the message is finally breaking through.

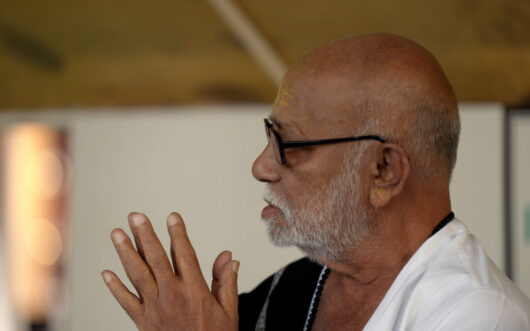

Morari Bapu is a spiritual leader who serves as an ambassador for the "Save the Whale Sharks" campaign in Gujarat, India.

Farukhkha Bloch is responsible for community outreach activities for the Wildlife Trust of India's Whale Shark Conservation Project.

To help India’s whale shark numbers recover, a program is now incentivizing fishermen to cut free the sharks from their nets — and offers to compensate the fishermen for the damages.

AI-enabled cameras are being deployed in a part of India that has the highest concentration of tigers on Earth. These trail cams don’t just take a photo of whatever passes by, but analyze it to identify whether it’s a tiger.

Dr. Hrishita Negi grew up watching wild tigers. Her father, Himmat, worked in tiger conservation for decades, contributing to India’s success in doubling its tiger population over the past 50 years.

The Klamath River dam removal — the largest such project in U.S. history — is nearing completion. Soon, salmon will swim freely in the river and its tributaries for the first time in over a century.

In the northeastern part of India, the population of greater adjutant stork had declined to just 115 birds — until biologist Purnima Devi Barman launched a grassroots effort to do bring the species back from the brink.

Dr. Purnima Devi Barman is a wildlife biologist and the founder of the Hargila Army, an all-female conservation initiative protecting the greater adjutant stork in Assam, India. Dr. Barman has received many awards in honor of her incredible conservation efforts. In 2017, she was the recipient of the Nari Shakti Puraskar award, which is the highest civilian […]

When an animal feeds primarily on dead or decaying matter, it is known as a scavenger. Scavengers — like vultures, hyenas, and raccoons — often have bad reputations due to their association with garbage and death. But they are actually an essential part of a functioning ecosystem. Scavengers are nature’s cleanup crew, eating parts of […]

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, often referred to simply as “the Red List,” ranks how close some 163,000 plants, animals, and other species are to extinction. Using the latest research, scientists assign a status to each listed species, ranging from “Least Concern” to “Endangered” to “Extinct.” The Red List was established in 1964 […]

Four community conservation tips from Whitley Award-Winner Purnima Devi Barman, founder of the Hargila Army.

To help protect an endangered stork, biologist Purnima Devi Barman provided looms and training to local women to create textiles and clothes that feature the bird.

The greater adjutant stork is one of the largest — and rarest — storks on earth. But locals in one of their last strongholds in Assam, India considered them to be a bad omen until Purnima Devi Barman revitalized their public image.

Bumble bee brigades help citizen scientists contribute to pollinator conservation, the NWF has tips to help local wildlife beat the heat, and plastic bags are down 80% on UK beaches.

It took 15 long months of trial and error to photograph mountain lion P-22 walking in front of the famed Hollywood sign.

The Santa Monica mountains near Los Angeles are home to a wide range of wildlife—including coyotes and mountain lions—all cut off from the rest of the world by the city’s massive freeways.

A lifelong advocate for wildlife, Beth Pratt has worked in environmental leadership roles for over thirty years.

Steve Winter is a wildlife photojournalist with decades producing stories for National Geographic Magazine and other outlets. He specializes in wildlife, and particularly, big cats.

Jeff Sikich is a wildlife biologist for the National Park Service researching the impacts of urbanization and habitat fragmentation on mountain lions in Southern California.

Frog saunas could help fight chytrid, Iberian lynx are no longer endangered, and scientists in Hawaii are breeding heat-resistant corals.

Boyan Slat is the founder and CEO of The Ocean Cleanup, a non-profit organization developing and scaling technologies to rid the world's oceans of plastic.

Alecia has held many career positions, from software trainer to office administrator; however, outside of work she is heavily involved in volunteer associations focusing on education. Most recently, Alecia’s Clean Harbours Jamaica team has, in partnership with The Ocean Cleanup, removed over 1 million kg of garbage from the barriers and by extension from the […]

It’s estimated that up to 14 million tons of plastic end up in the world’s oceans every year—and 80% of it pours into the sea from polluted rivers. In Kingston, Jamaica, Alecia Beaufort and her team at Clean Harbors Jamaica have partnered with The Ocean Cleanup to stop the waste before it ever reaches the sea.

Boyan Slat’s team at The Ocean Cleanup has developed and deployed an open-ocean system that can haul in 7000 kilos of garbage in just a day and a half. Their current target is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The hope is that a fleet of these systems will remove 90% of floating ocean plastic by 2040.

Golden eagles, bald eagles, and other North American raptors have made a remarkable comeback since the chemical pesticide DDT was banned in the United States in 1972. But they still face challenges to a full recovery. Learn more about golden eagles, and how you can support efforts to combat the threats they face.

Hannah was born and raised under the Big Sky in Montana and has enjoyed outdoor pursuits her whole life. With a bachelor’s in marketing and a master’s in resource conservation, she has a unique perspective on outreach efforts for the benefit of conservation.

For over 15 years, Bryan has been a leading scientist documenting the link between lead-based ammunition and ingestion in wildlife. He co-founded and is Director of Sporting Lead-Free to promote an unbiased, non-political message within our community about the benefits of using lead-free sporting options to preserve both our hunting heritage and amazing Wyoming wildlife.

Conservationist and hunter Bryan Bedrosian started Sporting Lead Free to offer a solution to the problem of lead poisoning in eagles: advocating for the use of non-lead bullets as a permanent substitute for traditional lead ammunition.

Nearly half of all golden eagles and bald eagles in the U.S. have elevated lead levels in their bodies. This lead poisoning comes from the bullets used by hunters — not because the bullets harm the eagles directly, but the birds do scavenge on “gut piles” laden with lead fragments left behind after successful hunts.

After years spend researching local wildlife, like the iconic cougar P-22, biologists around Los Angeles pinpointed the vital location for a wildlife crossing to be built to restitch an entire ecosystem.

At the age of 18, Boyan Slat founded The Ocean Cleanup and set out to clean plastic from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Ten years later, the team is installing catchment systems at the mouths of rivers to stop plastic pollution of the seas at their source.

Black-footed ferrets are still alive today thanks to the combined efforts of scientists, zoos, tribes, and other partners across North America. The work hasn’t been easy — it’s involved a decades-long captive breeding effort, wild releases at 30 different grassland sites, and even the development of a vaccine to protect against plague! It’s been a […]

Black-footed ferrets nearly went extinct several times in the 20th century. Today, the current largest threat to their survival is a non-native disease called sylvatic plague.

When plowing, poisoning, and non-native plague wiped out nearly 95% of prairie dogs, the ecosystem collapsed around them. Today, conservationists control the disease by providing vaccine-laden treats called “Fip Bits” to help the prairie dogs — and those that depend on them — finally rebound!

Golden eagles are powerful enough to hunt prey as large as deer, but they’re falling victim to deadly lead poisoning introduced to the wild by another potent hunter: us.

Black-footed ferrets have come back from near extinction thanks to breeding, cloning and reintroduction programs that have brought them back to the western prairie. Now, these wild populations are threatened by a plague that targets the prairie dogs they depend on for food — and even the ferrets themselves.

With over 25 years of experience in the wildlife field, Kristy Bly’s expertise is on the conservation and restoration of black-footed ferrets, black-tailed prairie dogs, and swift fox in the North American Great Plains.

Hope for Hawaiian honeycreepers, beavers in London, a snake's triumphant return, and rewilding on college campuses.

Fishing gear entanglement happens when fishing gear like nets and longlines gets caught around the limbs or body of an animal, causing serious injury or death.

Callie Veelenturf is a marine conservation biologist specializing in sea turtles, the founder of The Leatherback Project, and a National Geographic Explorer.

Aida Magaña Manzzo is a nautical engineer and community leader for the Saboga Wildlife Refuge. She has been recognized as a Hope Spot Champion for her marine conservation efforts in the Pearl Islands.

The Pearl Islands were a paradise off the Pacific coast of Panama, until industrial fishing fleets threatened fish stocks and endangered wildlife there. Local residents have teamed up with biologist Callie Veelenturf to propose—and pass—a new national law that grants legal rights to nature itself.

Marine biologist Callie Veenlenturf came to the Pearl Islands to study sea turtles, but soon helped spark passage of remarkable laws that grant legal rights to nature and the turtles themselves.

Sea otters are a marine mammal beloved by many, but it wasn't long ago that they teetered on the brink of extinction. The international fur trade decimated sea otter populations starting in the 1700s, and by the early 1900s, their wild population fell to less than 1% of their original numbers.

More than 35% of land in Belize is protected, and that’s been good for jaguars that live in these refuges — but for populations to thrive, the cats need to move from one safe area in the north to another in the south across a landscape of farms and towns.

Jaguars are top predators that need large spaces in which to live and hunt. In Belize, 35% of the land has been protected—but these areas are divided into two large clusters, connected by a crucial and dangerous bottleneck that the cats must navigate to survive.

Personhood for whales, a big conservation study, and egg-citing news for sea turtles

Emma Sanchez is a wildlife researcher and the country coordinator for Panthera Belize, an organization that pioneered jaguar research and established the first official protected area for jaguars.

Ray Cal is a wildlife ecologist and the manager of Runaway Creek Nature Reserve in central Belize. He is in charge of field operations and maintaining security, so that Runaway Creek continues to stay a model wildlife haven.

With just a few changes, you can transform your yard or balcony from a wildlife desert into a wildlife sanctuary. And, if you convince your neighbors to do the same, you could even make your neighborhood into a habitat corridor for wildlife!

Just like humans, wild animals often need to cross busy roads as they roam. But unlike us, they can’t rely on stoplights and crosswalks. That’s where wildlife crossings come in.

Wildlife corridors are an invaluable conservation tool. These ribbons of habitat connect landscapes fragmented by human development or roadways, giving animals the ability to roam in search of food, water, and mates.

Making and spreading seed balls (also called seed bombs!) like those seen in “Rebuilding a Forest” is a fun and easy way to kick-start a local rewilding project and help out native wildlife. Native flowers and grasses are essential building blocks that benefit the entire ecosystem — by attracting pollinators and providing the cover of […]

In Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, Mauricio Ruiz has turned his love for nature into action by working with the community to reforest a critical stretch of the nation’s most endangered forest, and by using drones to help him reach his goal of planting 15 million trees.

In order to scale up reforestation, Mauricio Ruiz and his organization ITPA have partnered with the drone fleet at MORFO. Each drone can plant up to 50 hectares of forest per day, which is 50 times faster than planting by hand.

Mauricio Ruiz grew up in the Atlantic Forest—one of the most biodiverse and threatened on Earth. At just 14 years old, he founded ITPA to fight back against rampant deforestation.

Planting native trees, grasses, and flowers is a great way to bolster biodiversity. Plants provide food and cover for animals and fungi, proving the foundation for healthy ecosystems.

Among the many benefits of healthy forests is their incredible ability to act as natural water filters. They do this in several ways. Leaves and branches in the forest canopy interrupt the fall of rainwater, slowing its progress and decreasing rainwater-driven erosion.

As a photographer, Rejane Duarte da Costa opened paths in her work in the environmental world as a field assistant and a hard worker. Seed collection and fire control were part of Rejane Duarte's daily routine until an opportunity arose to work in the nursery of the Instituto Terra de Protection Ambiental (ITPA).

Mauricio Ruiz is a political scientist and environmentalist renowned in Brazil. He is a winner of the Muriqui award, dedicated by UNESCO to personalities with great influence in the fight for biodiversity conservation.

In the past 40 years, golden lion tamarins became a symbol of conservation success when 150 zoos worldwide assisted a breeding and reintroduction program that brought their numbers in the wild from 200 to over 3700. Then, yellow fever jumped from humans to the primates and began to decimate their population—taking a third of the population in just two years.

Golden lion tamarins were nearly wiped out in the 1970s, but worldwide efforts by 150 zoos helped bring the species back from near-extinction. Today, local conservationists are expanding the forests in Brazil, and the wild population has grown from under 200 to now over 4800 tamarins!

Andreia started working with the conservation of the golden lion tamarin in 1983 as a volunteer in environmental education actions. In 1984, she became part of the golden lion tamarin reintroduction team. She is currently the coordinator of the field management of golden lion tamarins.

Zoos may be places where you can catch a glimpse of your favorite animal on a day out, but increasingly, they play an even more important role: as conservation institutions.

Deep in the Panamanian forest, researchers are looking for “lost frogs” — species believed to have gone extinct, but that may be holding on in the wild.

In the heart of Panama, scientists have created an artificial rainforest to protect endangered frogs from the worst wildlife disease ever recorded.

Harlequin frogs (also called harlequin toads) are a group of beautiful, brightly-colored toads found in Central and South America. One species in particular, the Panamanian golden frog, is considered the national animal of Panama and a flagship species for amphibian conservation.

Dr. Gina Della Togna is the Executive Director of the Amphibian Survival Alliance and a Research Associate of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Brian Gratwicke is a conservation biologist who leads the amphibian conservation programs at Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute.

Smack-dab in the middle of Rio de Janeiro, stands the world’s largest urban rainforest…and it needs our help. To combat a century of deforestation and hunting, a team of researchers are repairing the forest’s forgotten web of life, one species at a time.

When a habitat looks lush but is actually devoid of much of its native wildlife, it is sometimes called a green desert. A green desert might refer to a field planted with a single crop (called “monoculture”) or a forest planted with just one or several tree species.

Plants can’t move on their own, so they usually need a little help to spread their seeds far and wide. Animals that scatter these seeds — often by eating the fruit and pooping out the remains — are known as seed dispersers.

Alexandra Pires is currently an associate professor at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro, where she teaches the subjects of Natural Resources Conservation and Fauna Management.

Marcelo Rheingantz is a biologist at the Institute of Biology, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and Executive Director of Refauna. He has dedicated his research career to the ecology and conservation of vertebrate populations in Brazil and South America.

In 2010, Fernando launched the concept of refaunation, and from then on coordinated the Refauna project, which reintroduced populations of agoutis, howler monkeys and tortoises in the Tijuca National Park, in Rio de Janeiro.

To restore the park to its former glory, researchers knew which animals needed to be reintroduced: monkeys, rodents, tortoises, and even dung beetles all played crucial roles in keeping the forest healthy.

Agoutis are large, adorable rodents found in Central and South America – and they’re critical players in keeping forest ecosystems healthy.

Brazil is a trove of biodiversity — habitats like the Atlantic Rainforest, urban forests like Tijuca National Park, and more coastlines, rainforests, and rivers that are rich with endemic plants and wildlife.

Over 50 species of honeycreeper once lived in Hawai’i, but now only 17 species remain after battling against invasive species and habitat loss. Today, even those survivors are threatened further by avian malaria. To stop the disease, conservationists use innovative techniques to suppress the population of the invasive mosquitoes that spread it.

Millions of years ago, a single rosefinch species arrived on the Hawai’ian islands and evolved into over 50 species of honeycreepers — a phenomenon known as adaptive radiation.

Hawaiian honeycreepers are a group of songbirds endemic to the Hawaiian islands, all descended from a single species that arrived from the mainland six to seven million years ago. They are considered a dramatic example of adaptive radiation, a phenomenon in which a single species rapidly diversifies into many different ones. At one point, there were more than 50 different honeycreeper species on the islands, each sporting its own unique coloration, beak shape, and diets.

One of the major threats to Hawaiian honeycreepers is a deadly, mosquito-borne disease called avian malaria. Similar to malaria that infects humans, the disease is caused by parasites that enter honeycreepers’ bloodstreams when they are bitten by a disease-carrying mosquito.

Hawai’i is home to a broad, beautiful array of birds species found only on its islands—like the stunningly diverse honeycreepers, many on the border of extinction. Now, a local team is removing invasive predators, restoring habitats, and battling mosquito-borne diseases to protect honeycreepers from their latest threat: avian malaria.

Christa Seidl is a disease ecologist with over 10 years of experience leading research and conservation projects in Hawai'i, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Madagascar, Ecuador, and California with private, public, and industry partners.

Laura Bertholdis an Avian Research Field Supervisor at the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project (MFBRP) assisting with planning and implementing research and management projects for native honeycreeper and forest recovery.

In addition to the impact of avian malaria, Hawai’i’s endangered honeycreepers are threatened by habitat loss and invasive predators — two problems that harm native bird populations everywhere, likely in your own back yard. Whether you’re looking to help Hawai’i’s birds, or if you’re hoping to make a difference to protect birds locally, the solutions […]

New tracking technologies are uncovering the flight paths of endangered shorebirds — and the obstacles they face along the way.

The endangered wedge-tailed shearwater — also known as the ‘ua‘u kani — was in critical danger after many nesting sites in Hawaii were overrun by predators like weasels, rags, or feral cats. Fortunately for the birds, locals banded together to protect nesting sites and the local population went from just 30 nesting birds to more than 3000!

A group in Maui has restored a safe haven for endangered seabirds to come home and nest: it’s completely fenced-off from predators and restored with native plants, but the birds still need some convincing! The team is using decoy “neighbors” and audio recordings of bird calls to make the seabirds feel at home — and at long last, the colony is growing!

All around the world, seabirds provide a critical link between land and sea. On Hawai’i, ecologists are working to protect two vital shearwater species that helped life first take hold on these islands.

Seabirds like those in Hawai'i have been given a second chance by the volunteers, scientists, and communities that lead the work to reverse their decline. While these birds — and the threats they face — may be unique to islands in the Pacific, the work to protect birds of a feather can be found anywhere around the globe.