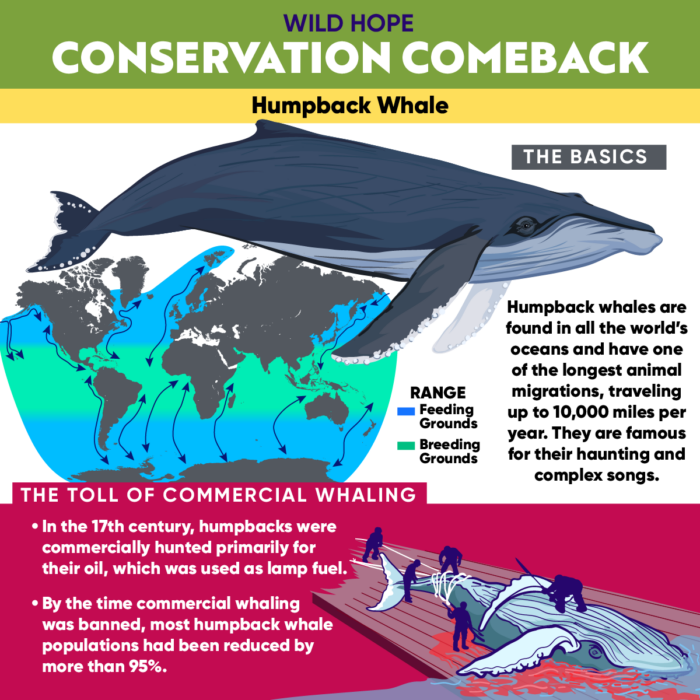

Humpback whales are truly a global species. These mammals have one of the longest migrations around, traveling up to 10,000 miles in a single year — and their beautiful, complex songs are heard by sailors and tourists in every corner of the map. Throughout the 17th century, humpback whales were hunted primarily for their oil to use as a lamp fuel. By the time whaling was officially banned, humpback populations worldwide had been reduced by 95%.

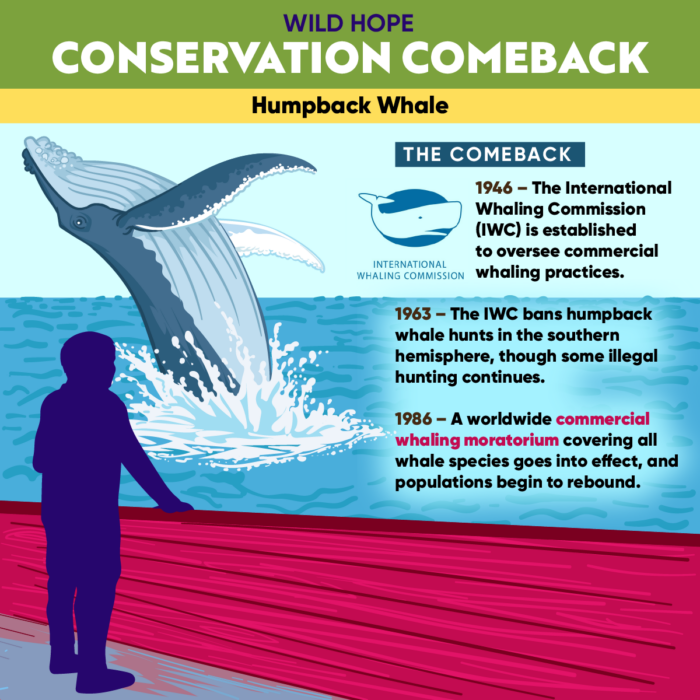

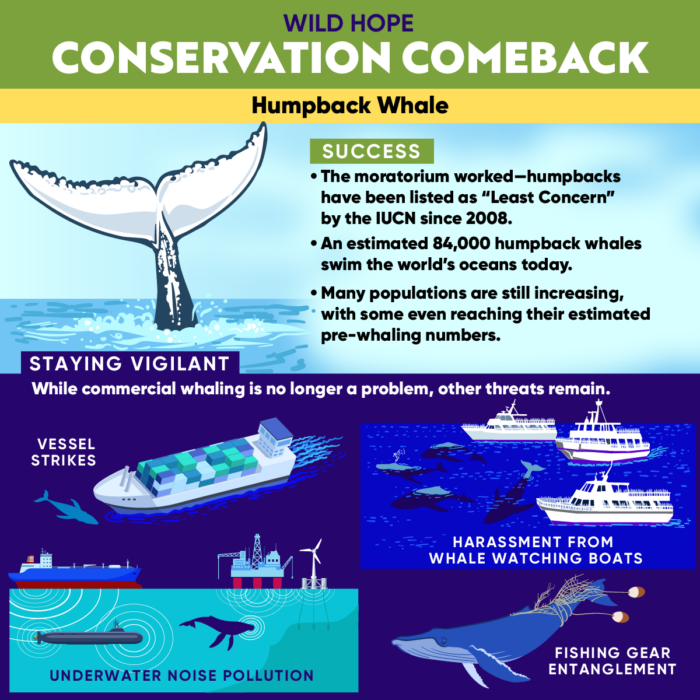

The comeback was slow, but began in 1946 with the establishment of the International Whaling Commission to oversee whaling practices. Hunting humpbacks was officially banned in 1963, and in 1986, a worldwide commercial whaling moratorium gave populations another foothold on the path to recovery. Today, an estimated 84,000 humpbacks swim the world’s oceans, and many populations are still on the rise, even approaching their pre-whaling numbers.

Explore more stories from the full Conservation Comeback series now.

The mountain gorilla, a critically endangered subspecies of the eastern gorilla, has faced a dramatic decline over the past century. By the early 20th century, their population had dwindled due to habitat loss, poaching, and the spread of diseases from humans. At its lowest point in the 1980s, the mountain gorilla population was reduced to fewer than 250 individuals, with their survival hanging by a thread.

With its growing population and wealth of wildlife, India is at the forefront of creative, community-based solutions to human-wildlife conflict.

Using satellite trackers, scientists have discovered the whereabouts of young sea turtles during a key part of their lives.

For decades, conservationists have pushed for changes to U.S. 64, a busy two-lane highway to the popular Outer Banks that runs straight through the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge — one of just two places in the world where red wolves run free. They may finally be getting their wish.

Brazil's Atlantic Forest is often shadowed by the vast Amazon, but it is just as biodiverse and at greater risk of vanishing without conservation action.

The Hawaiian archipelago is a tropical volcanic island chain with high biodiversity on land and in the surrounding waters of the Pacific Ocean. The mountainous terrain is home to many species found nowhere else on Earth, including 5000 insect species, 1000 plant species, 145 fish species, and 60 bird species. But Hawai’i’s wildlife has been […]

About 21.5 million acres of the Western United States are nationally protected, and thousands are being managed or co-managed by Native American tribes reclaiming ancestral relationships with native plants and animals. It’s no surprise, then, that Wild Hope hit a rich vein of conservation stories grounded in the West.

The smaller and rarer of the two African rhino species, the black rhinoceros has faced steep decline since the early 20th century.

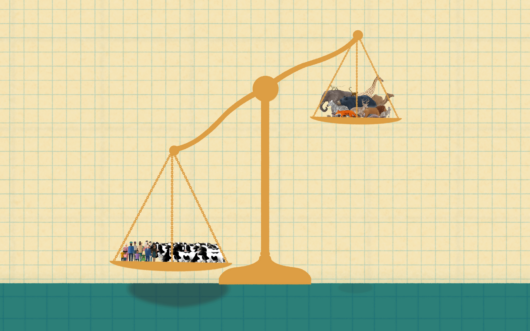

The planetary impact of largescale animal agriculture on biodiversity is immense – from the release of greenhouse gases, to the demand for available land at the expense of native ecosystems. Studies show that 75% of all agricultural land on earth is committed to raising livestock, and replacing meat products with plant-based foods could free up […]

Innovative biochemist Pat Brown is the man behind the Impossible Burger. Now, he's set his sights on a rewilding project on a ranch in Arkansas.

Efforts to break our dependence on large-scale animal agriculture are real… and they're working on two fronts! First to create alternative options for protein that don't come from animals, and second, to transform defunct cattle ranches into revived forested ecosystems.

Bringing biodiversity back to a clearcut ranch in Arkansas is a daunting task, but the mission is clear: use trees and native plants as powerful tools for capturing and sequestering carbon.

It was a late-career epiphany that led “wacky genius” Pat Brown to abandon his academic career and commit himself to fighting global warming and biodiversity collapse. He did it, against all odds, by developing a surprising product: the revolutionary and delicious plant-based Impossible Burger.

Two Wild Hope episodes filmed in Gorongosa National Park and produced by NEWF African Science Film Fellows provide a model for empowering local film crews.

Economic growth and wildlife conservation often run in conflict, but Mozambican scientist Cesária Huo hopes to support a new sustainable and economically viable model for harvesting a potent natural resource: bat guano.

To successfully protect the wildlife in Gorongosa National Park, biologists like Cesária Huo know to first support the communities that call the park home.

Researchers survey the bats in Mozambique's Cheringoma caves looking for insectivorous species known to produce the best quality guano that can be harvested as fertilizer.

Cesaria Huo is a conservation biologist focusing on bat research in Gorongosa National Park.

Pangolins are the only scaled mammal on earth, and unfortunately this unique and beautiful feature is the target of poachers and illegal animal traders seeking the scales for use in traditional medicine.

Pangolins are amazing, bizarre creatures that live in Central and Southern Africa. They feed exclusively and voraciously on ants and termites, and they’re perfectly specialized for this type of hunt.

Pangolins are the only scaled mammal on Earth. Unfortunately, this unique and beautiful feature is the target of poachers and illegal animal traders, who seek the scales for use in traditional medicine.

Shajan M.A. is a sociologist who has worked with Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) for the last 11 years. He joined as a Field Officer at the Elephant Corridor Securement Project in Wayanad, Kerala. He completed his post-graduate degree in social work from the University of Calicut, Kerala, and M.Phil. in psychiatric social work from […]

Jose Louise is the CEO of Wildlife Trust of India (WTI).

Protecting the migratory corridors for India's elephants benefits countless other plants and animal as well, making elephants an “umbrella species” whose protection benefits other wildlife that shares the same ecosystem.

In southern India, villages were built in the middle of an “elephant superhighway” used by the largest population of Asian elephants on Earth, leading to ongoing conflict that was dangerous for both the human residents and the elephants themselves.

It hasn’t been easy to convert the fishing community of Gujarat, India to be whale shark allies — but the message is finally breaking through.

Morari Bapu is a spiritual leader who serves as an ambassador for the "Save the Whale Sharks" campaign in Gujarat, India.

Farukhkha Bloch is responsible for community outreach activities for the Wildlife Trust of India's Whale Shark Conservation Project.

To help India’s whale shark numbers recover, a program is now incentivizing fishermen to cut free the sharks from their nets — and offers to compensate the fishermen for the damages.

In Madhya Pradesh, renowned as India’s “tiger state,” a team installs AI-integrated camera traps to reduce conflict and safeguard lives in a vital wildlife corridor home to 2 million people – and 300 wild tigers.

Piyush Yadav is a Conservation Technology Fellow at RESOLVE, where he focuses on developing and implementing new technologies for wildlife protection.

Dr. Himmat Singh Negi is a retired Indian Forest Service Officer who has spent more than three decades in the field of Tiger Conservation and related conflict mitigation.

Hrishita Negi is a Ph.D. candidate at Clemson University undertaking her research in the globally recognized tiger landscape of Central India.

AI-enabled cameras are being deployed in a part of India that has the highest concentration of tigers on Earth. These trail cams don’t just take a photo of whatever passes by, but analyze it to identify whether it’s a tiger.

Dr. Hrishita Negi grew up watching wild tigers. Her father, Himmat, worked in tiger conservation for decades, contributing to India’s success in doubling its tiger population over the past 50 years.

Tigers are one of the most iconic faces of wildlife conservation worldwide. These species are still endangered, but indeed on the rise — although it wasn't long ago that tiger populations teetered on the edge of extinction.

When an animal feeds primarily on dead or decaying matter, it is known as a scavenger. Scavengers — like vultures, hyenas, and raccoons — often have bad reputations due to their association with garbage and death. But they are actually an essential part of a functioning ecosystem. Scavengers are nature’s cleanup crew, eating parts of […]

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, often referred to simply as “the Red List,” ranks how close some 163,000 plants, animals, and other species are to extinction. Using the latest research, scientists assign a status to each listed species, ranging from “Least Concern” to “Endangered” to “Extinct.” The Red List was established in 1964 […]

Bumble bee brigades help citizen scientists contribute to pollinator conservation, the NWF has tips to help local wildlife beat the heat, and plastic bags are down 80% on UK beaches.

It took 15 long months of trial and error to photograph mountain lion P-22 walking in front of the famed Hollywood sign.

The Santa Monica mountains near Los Angeles are home to a wide range of wildlife—including coyotes and mountain lions—all cut off from the rest of the world by the city’s massive freeways.

A lifelong advocate for wildlife, Beth Pratt has worked in environmental leadership roles for over thirty years.

Steve Winter is a wildlife photojournalist with decades producing stories for National Geographic Magazine and other outlets. He specializes in wildlife, and particularly, big cats.

Jeff Sikich is a wildlife biologist for the National Park Service researching the impacts of urbanization and habitat fragmentation on mountain lions in Southern California.

Frog saunas could help fight chytrid, Iberian lynx are no longer endangered, and scientists in Hawaii are breeding heat-resistant corals.

Around ten million tons of plastic enter the world's oceans each year. Learn about a few of the ways that YOU can help reduce ocean plastic.

Boyan Slat is the founder and CEO of The Ocean Cleanup, a non-profit organization developing and scaling technologies to rid the world's oceans of plastic.

Alecia has held many career positions, from software trainer to office administrator; however, outside of work she is heavily involved in volunteer associations focusing on education. Most recently, Alecia’s Clean Harbours Jamaica team has, in partnership with The Ocean Cleanup, removed over 1 million kg of garbage from the barriers and by extension from the […]

It’s estimated that up to 14 million tons of plastic end up in the world’s oceans every year—and 80% of it pours into the sea from polluted rivers. In Kingston, Jamaica, Alecia Beaufort and her team at Clean Harbors Jamaica have partnered with The Ocean Cleanup to stop the waste before it ever reaches the sea.

Boyan Slat’s team at The Ocean Cleanup has developed and deployed an open-ocean system that can haul in 7000 kilos of garbage in just a day and a half. Their current target is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The hope is that a fleet of these systems will remove 90% of floating ocean plastic by 2040.

After years spend researching local wildlife, like the iconic cougar P-22, biologists around Los Angeles pinpointed the vital location for a wildlife crossing to be built to restitch an entire ecosystem.

At the age of 18, Boyan Slat founded The Ocean Cleanup and set out to clean plastic from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Ten years later, the team is installing catchment systems at the mouths of rivers to stop plastic pollution of the seas at their source.

Black-footed ferrets are still alive today thanks to the combined efforts of scientists, zoos, tribes, and other partners across North America. The work hasn’t been easy — it’s involved a decades-long captive breeding effort, wild releases at 30 different grassland sites, and even the development of a vaccine to protect against plague! It’s been a […]

Black-footed ferrets nearly went extinct several times in the 20th century. Today, the current largest threat to their survival is a non-native disease called sylvatic plague.

When plowing, poisoning, and non-native plague wiped out nearly 95% of prairie dogs, the ecosystem collapsed around them. Today, conservationists control the disease by providing vaccine-laden treats called “Fip Bits” to help the prairie dogs — and those that depend on them — finally rebound!

Black-footed ferrets have come back from near extinction thanks to breeding, cloning and reintroduction programs that have brought them back to the western prairie. Now, these wild populations are threatened by a plague that targets the prairie dogs they depend on for food — and even the ferrets themselves.

With over 25 years of experience in the wildlife field, Kristy Bly’s expertise is on the conservation and restoration of black-footed ferrets, black-tailed prairie dogs, and swift fox in the North American Great Plains.

Hope for Hawaiian honeycreepers, beavers in London, a snake's triumphant return, and rewilding on college campuses.

Fishing gear entanglement happens when fishing gear like nets and longlines gets caught around the limbs or body of an animal, causing serious injury or death.

Callie Veelenturf is a marine conservation biologist specializing in sea turtles, the founder of The Leatherback Project, and a National Geographic Explorer.

Aida Magaña Manzzo is a nautical engineer and community leader for the Saboga Wildlife Refuge. She has been recognized as a Hope Spot Champion for her marine conservation efforts in the Pearl Islands.

Panama recognizes the rights of sea turtles under national law, including their right to a healthy environment. To figure out which places are critical to the turtles’ well-being, biologist Callie Veelenturf and children from affected communities are tagging dozens of turtles and tracking them by satellite.

The Pearl Islands were a paradise off the Pacific coast of Panama, until industrial fishing fleets threatened fish stocks and endangered wildlife there. Local residents have teamed up with biologist Callie Veelenturf to propose—and pass—a new national law that grants legal rights to nature itself.

Marine biologist Callie Veenlenturf came to the Pearl Islands to study sea turtles, but soon helped spark passage of remarkable laws that grant legal rights to nature and the turtles themselves.

Sea otters are a marine mammal beloved by many, but it wasn't long ago that they teetered on the brink of extinction. The international fur trade decimated sea otter populations starting in the 1700s, and by the early 1900s, their wild population fell to less than 1% of their original numbers.

More than 35% of land in Belize is protected, and that’s been good for jaguars that live in these refuges — but for populations to thrive, the cats need to move from one safe area in the north to another in the south across a landscape of farms and towns.

Conservationists worldwide use camera traps to study the movements of wild animals. In Belize, they’ve deployed one of the longest-running grids of cameras on the planet to track the hidden lives of jaguars and to focus protections in the dwindling rainforest.

Jaguars are top predators that need large spaces in which to live and hunt. In Belize, 35% of the land has been protected—but these areas are divided into two large clusters, connected by a crucial and dangerous bottleneck that the cats must navigate to survive.

Personhood for whales, a big conservation study, and egg-citing news for sea turtles

Emma Sanchez is a wildlife researcher and the country coordinator for Panthera Belize, an organization that pioneered jaguar research and established the first official protected area for jaguars.

Ray Cal is a wildlife ecologist and the manager of Runaway Creek Nature Reserve in central Belize. He is in charge of field operations and maintaining security, so that Runaway Creek continues to stay a model wildlife haven.

Brazil has over a million miles of roads, and Fernanda Abra has devoted herself to making them less dangerous to local wildlife and biodiversity.

With just a few changes, you can transform your yard or balcony from a wildlife desert into a wildlife sanctuary. And, if you convince your neighbors to do the same, you could even make your neighborhood into a habitat corridor for wildlife!

Just like humans, wild animals often need to cross busy roads as they roam. But unlike us, they can’t rely on stoplights and crosswalks. That’s where wildlife crossings come in.

Fernanda Abra is a biologist with a Ph.D. in Applied Ecology and is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Smithsonian Conservation and Sustainability Center.

Wildlife corridors are an invaluable conservation tool. These ribbons of habitat connect landscapes fragmented by human development or roadways, giving animals the ability to roam in search of food, water, and mates.

The Brazilian treetops are full of creatures like monkeys and sloths living high above a forest floor segmented by dangerous roadways. The Via Fauna team is installing arboreal crossings made of cheap, local materials to reconnect the forest canopy — and allow these creatures to once again move freely throughout their landscape.

Brazil has more biodiversity than any other nation on Earth, but it also has more than a million miles of roads. Biologist Fernanda Alba and her team are establishing underpasses across the country that allow big terrestrial animals — to date, the team has documented over 40,000 safe wildlife crossings.

In the past 40 years, golden lion tamarins became a symbol of conservation success when 150 zoos worldwide assisted a breeding and reintroduction program that brought their numbers in the wild from 200 to over 3700. Then, yellow fever jumped from humans to the primates and began to decimate their population—taking a third of the population in just two years.

Golden lion tamarins live only in small fragments of the Atlantic Forest. In 2021, an outbreak of yellow fever took nearly one third of the already endangered population, but teams were able to modify a vaccine for humans to help immunize the population against future outbreaks.

Golden lion tamarins were nearly wiped out in the 1970s, but worldwide efforts by 150 zoos helped bring the species back from near-extinction. Today, local conservationists are expanding the forests in Brazil, and the wild population has grown from under 200 to now over 4800 tamarins!

Conservationists are hard at work protecting golden lion tamarins and other wildlife from extinction, and now you can help them from the comfort of your own home.

Andreia started working with the conservation of the golden lion tamarin in 1983 as a volunteer in environmental education actions. In 1984, she became part of the golden lion tamarin reintroduction team. She is currently the coordinator of the field management of golden lion tamarins.

Marcos da Silve Freire has more than 30 years of experience in microbiology, with an emphasis on vaccinology. He is responsible for developing the yellow fever vaccine for golden lion tamarins.

Luís is a geographer who graduated from São Paulo University in 1987. He began his career working for natural areas protected by heritage in São Paulo, especially Serra do Mar.

Smack-dab in the middle of Rio de Janeiro, stands the world’s largest urban rainforest…and it needs our help. To combat a century of deforestation and hunting, a team of researchers are repairing the forest’s forgotten web of life, one species at a time.

Plants can’t move on their own, so they usually need a little help to spread their seeds far and wide. Animals that scatter these seeds — often by eating the fruit and pooping out the remains — are known as seed dispersers.

Alexandra Pires is currently an associate professor at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro, where she teaches the subjects of Natural Resources Conservation and Fauna Management.

Marcelo Rheingantz is a biologist at the Institute of Biology, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and Executive Director of Refauna. He has dedicated his research career to the ecology and conservation of vertebrate populations in Brazil and South America.

In 2010, Fernando launched the concept of refaunation, and from then on coordinated the Refauna project, which reintroduced populations of agoutis, howler monkeys and tortoises in the Tijuca National Park, in Rio de Janeiro.

To restore the park to its former glory, researchers knew which animals needed to be reintroduced: monkeys, rodents, tortoises, and even dung beetles all played crucial roles in keeping the forest healthy.

Agoutis are large, adorable rodents found in Central and South America – and they’re critical players in keeping forest ecosystems healthy.

Brazil is a trove of biodiversity — habitats like the Atlantic Rainforest, urban forests like Tijuca National Park, and more coastlines, rainforests, and rivers that are rich with endemic plants and wildlife.

Jay Penniman has worked as an independent contractor doing forestry, wildlife, and vegetation surveys, management, and assessment. Since 2006, he has worked for the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit of the University of Hawaii managing the Maui Nui Seabird Recovery Project.

Jenni Learned is a broad-spectrum ecologist on the Maui Nui Seabird team with experience working across diverse environments.

A common conservation technique on islands is the creation of predator-free zones to exclude invasive species, from mice to feral pigs, from recovering habitats.

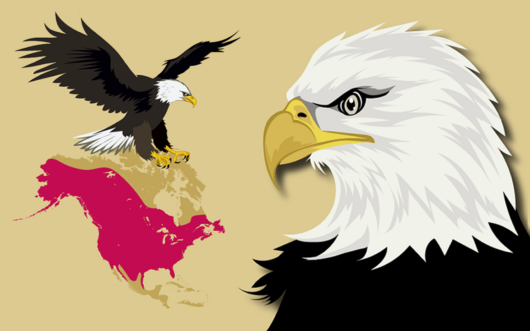

The bald eagle has been a national symbol of the United States since 1782 — but not that long ago, this iconic species was on the verge of a complete extinction.

Researchers are trumpeting a welcome piece of news for African elephants. In the last 25 years, populations in southern Africa have reversed their declines, and even started to grow, according to a new study in Science Advances.

Coral reefs around the world are threatened by rising ocean temperatures, but hope is growing off the coast of Hawaii. There, researchers at the Coral Resilience Lab selectively breed corals to withstand ever-increasing amounts of heat stress.

This community in Hawaii is rallying together to study and protect local corals. Students, volunteers, and scientists work to collect and categorize fragments broken off from the reef, which then become candidates to breed before the new coral is reintroduced back into the ocean.

Corals are vital to ocean health, but they’re susceptible to rising water temperatures and can “bleach” under too much heat stress. Hawaii’s Coral Resilience Lab is breeding corals that are resilient to these hotter ocean temperatures – then they populate reefs with new corals that can finally beat the heat.

Coral reef bleaching stands apart as a crisis with innovative, long-term solutions.

Kira Hughes is the Managing Director of the Coral Resilience Lab at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology. This includes conducting research, grant writing and administration, engaging stakeholders, establishing and maintaining partnerships, and communicating science.

Madeleine Sherman is the Project Manager for the Coral Resilience Lab at the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology, and manager of the Lab's outreach and education programs.

Corals are known for their vibrant hues, but when they get stressed, they turn a ghostly white in a process known as coral bleaching. To appreciate why this happens, you need to understand the unique relationship that forms the basis of coral reefs.

The California condor is a North American wildlife icon — the continent's largest land birds and one of nature's most industrious scavengers — and also one of our most critically endangered avian species.

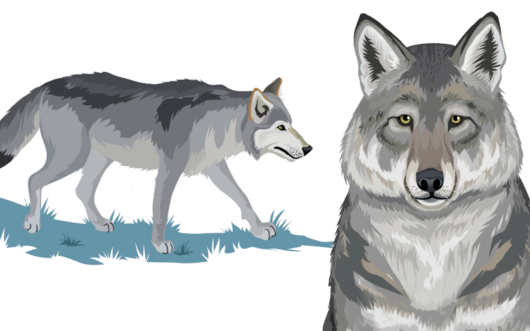

Our relationship with gray wolves is a complicated one, spanning centuries of tension and dating back to the beginning in the 1600s with North American colonization.

The recovery of the American Alligator is considered one of the biggest success stories of an endangered species – ever.

Along the Pacific coastlines of North America, the Northern Elephant Seal may be a common sight in today's waters — but that wasn't always the case.

Florida manatees are in dire straits, having lost much of their available habitat and food sources in recent decades. Thanks to the work of Zoo Tampa and other researchers, the population is finally able to recover and return to the rivers they once called home.

Florida’s Crystal River used to be a rich seagrass ecosystem: a perfect source of food for the many manatees that once thrived there, before an invasive algae overtook the riverbed. Now, efforts to restore the habitat are underway – and they’re working!

When an invasive algae in Crystal River wiped out the eel grass that manatees need for food, the community rallies to restore the river and save the animals that call it home.

Lisa Moore, a fourth-generation Floridian, is an entrepreneur and philanthropist dedicated to the efforts to preserve, protect, and restore environmental resources.

Jessica Maillez is the Senior Environmental Manager at Sea and Shoreline. She has designed, permitted, and managed multiple large scale restoration projects along Florida’s coastline.

The United Kingdom and Ireland might not seem like the wildest places on Earth, but a growing popular movement here, known as rewilding, seeks to reverse millennia of environmental degradation.

Derek Gow has turned his farm into a breeding center to help rewild all of Britain. He’s raising rare white storks, native harvest mice, water voles that can help restore wetlands throughout the country.

Derek Gow has helped bring beavers back to Britain, and their impact on local landscapes and biodiversity has been immense. Now, he’s scaling up a breeding program to export another wetland engineer—the water vole—all across the country.

For years, Derek Gow worked his 400-acres in western England as a conventional sheep and cattle farm. Now, he’s using his experience with British rewilding projects to return his land to what it once was: a healthy, biodiverse ecosystem.

Pete Cooper is a wilding ecologist at the Derek Gow Consultancy, where he works on a variety of species reintroduction and rewilding projects. He leads a project trialing the captive breeding and reintroduction of glowworms, as well as working closely on reintroduction projects for other species including the harvest mouse, wildcat and turtle dove.

Derek Gow is a farmer, nature conservationist, and the author of Bringing Back the Beaver. He lives on a 300-acre farm on the Devon/Cornwall border, which he is in the process of rewilding. Derek has played a significant role in the reintroduction of the Eurasian beaver, the water vole and the white stork in England.

Often the first and most effective strategy to healing a landscape is to pay attention to how ancestral wildlife, like native plants and animals, once shaped and strengthened these natural spaces.