A taste for waste turns these creatures into pollution-fighting machines

To a hungry human, a platter of fresh oysters might be a delicious treat. But to an oyster, a dirty harbor is the real feast. Oysters literally eat up the algae, food waste, and sewer sludge that can turn clear waters into murky soups. And their taste for waste has a healthy side effect—some 200 species of oyster filter trillions of gallons of water in estuaries and coastal waters across the globe. Now, conservationists are trying to harness this “superpower” to clean some of the world’s most polluted harbors and bays.

What are oysters?

Oysters are bivalves, meaning their soft bodies are encased in hinged shells. They are also filter feeders, a diverse group of animals that includes sponges, flamingos, and baleen whales. These creatures eat by pulling water through their bodies and across specialized feeding organs—and then pushing out the leftovers.

How do they fight pollution?

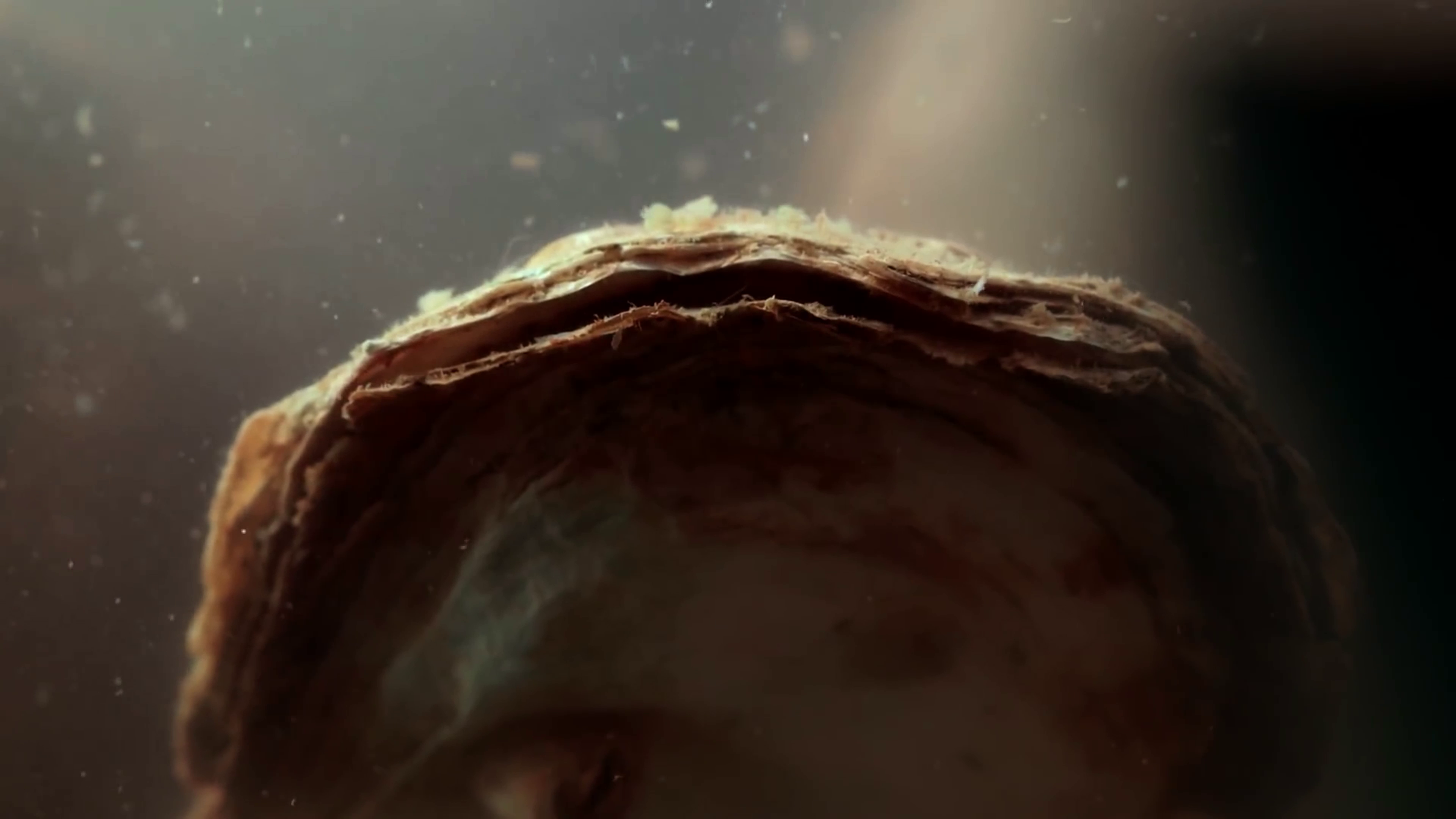

Wrapped within an oyster’s tough shell are delicate layered gills used for breathing and feeding. Miniscule hairlike structures called cilia line these gills and guide plankton and algae into the mollusk’s mouth. They also catch other gunk dirtying the water column, like nitrogen, sediment, and even metals.

In the oyster’s gills, the food and particles stick to mucus, just like bugs on flypaper. Next, they ooze down into the oyster’s digestive system. Excess nitrogen is incorporated into the oyster’s body, and any particles the oyster can’t eat get expelled in mucus-coated “pseudofeces.” The excrement falls out of the water column and collects on the ocean floor. The remaining water cycles out, just like clean water through a kitchen filter.

In waters full of storm drain overflow and nitrogen runoff, oysters can be efficient clean-up crews. The average adult oyster, which is about the size of a computer mouse, can filter up to 12.5 gallons of dirty water in 24 hours. That works out to nearly a bathtub’s worth in three days! In one study, biologists estimated that the oysters of the Chesapeake Bay could once filter the Bay’s whole water column in less than a week. But that was in the mid-1800s, before humans decimated their population.

How are conservationists harnessing oysters’ superpowers?

Oyster populations have plummeted since the late 1800s—a 2011 study estimated that nearly 85% of the world’s oyster reefs have been lost. Worried about ocean pollution and biodiversity loss, U.S. conservationists are now putting to work the two oyster species native to U.S. waters: the Atlantic or eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) and the Pacific-dwelling Olympia oyster (Ostrea lurida).

On the West Coast, the Puget Sound Restoration Fund in Washington state has cultivated 100 acres of Olympia oyster reefs. On the East Coast, the Billion Oyster Project wants to introduce a billion eastern oysters into New York Harbor by 2035. The group has already “seeded” 100 million of these filtering machines in bays, basins, and on the bases of bridges around the city. (You can see them in action in “The Big Oyster” here.) And Maryland’s Oyster Recovery Partnership has introduced a whopping 10 billion oysters to the Chesapeake Bay since 1994.

And those efforts are yielding results: Studies at one of the Oyster Recovery Partnership’s 350-acre reefs suggest its tiny superheroes are removing 20,000 pounds of nitrogen a year—that’s more than seven times the amount in oyster-less waters.

Want to restore oyster reefs?